Gaming is a new industry in many people’s minds, but it’s actually decades old. The games that have been produced in the past few decades are vast. There are many famous masterpieces that are very popular. The latecomers have never heard of them. As the developers leave, change careers, and die, the company closes down, is acquired, and various copyrights, privacy protection, etc. The problem, many of these games have faded into history. In recent years, more people have begun to pay attention to the topic of old game preservation. However, the intensity of protection is far less than that of the fast-growing industry itself.

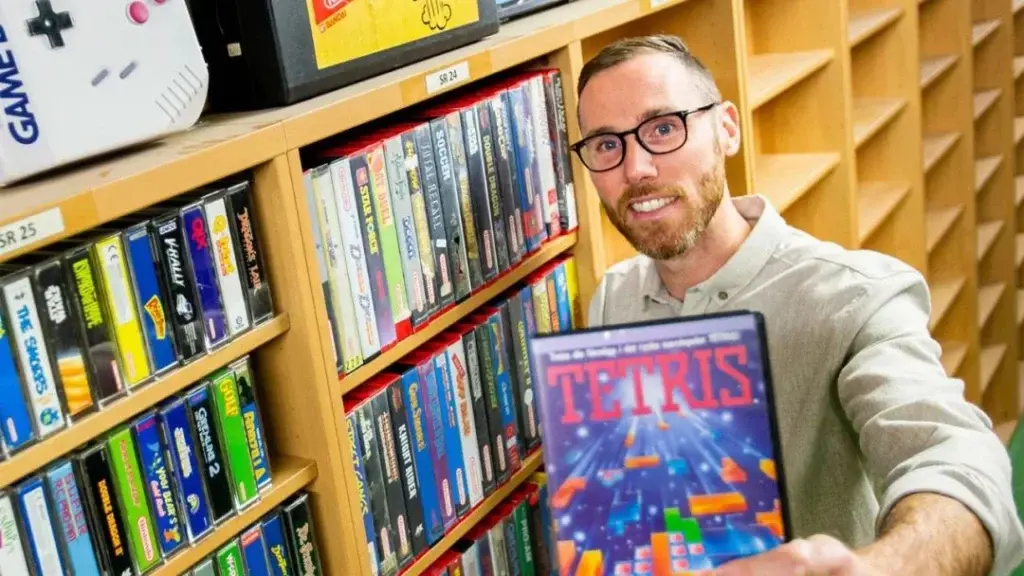

“We need more people, more people,” said Andrew Berman, curator of digital games at The Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, N.Y. Time and money. As more games come out, we definitely need more people and time to preserve them.”

Berman has worked for the museum for 5 years. However, for the past nearly 20 years, he has been dedicated to preserving old games. The museum’s collection of approximately 65,000 game-related items includes thousands of magazines, books, catalogues, and other print items. He believes that with the rise of digital games, game custodians will face a new set of challenges.

“If you look at physical retail games before the PS4 or Xbox One days, people kept them pretty well. You could find a lot of copies on the market. There are exceptions of course like some were only available digitally…the physical game preservation is easy and will not disappear completely.”

Challenges posed by digital distribution

Game preservation is not as easy as many people believe. “Today, some physical games don’t provide the full content. Instead, they provide the player with an activation key for the downloadable version, or continuously update the version through download,” Berman said. “This means that the physical copy is no longer a save game”

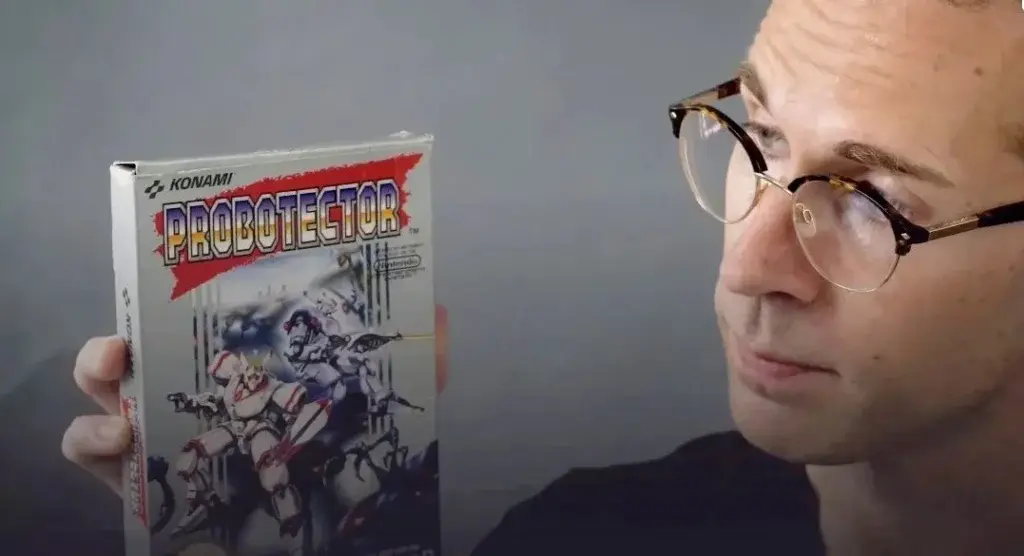

Chris Young, director of the Syd Bolton Collection at the University of Toronto, Mississauga, feels the same way. In 2018, after the death of game collector Cyd Bolton, the University of Mississauga acquired the collection. As of now, the museum has about 14,000 games, more than 5,000 magazines, and a lot of other materials.

“It used to be a matter of getting a cassette or disc, but now it’s a lot harder to save old games,” Young added. “The environment has changed, and the game is almost always being updated…In a way, considering the game changes over time, it’s almost impossible for you to keep them intact. For example, a mobile game has been out for 10 years, and it’s likely to look very different from when it was first released. This is because of the regular updates and changes in storylines…”

Even if the developer has a backup of all versions on hand it does not solve the problem. This is because there will likely be an update to the hardware and software that supports the game. Thus, game preservation will be difficult. Opening the game will also be another challenge. In addition, many APIs are out of the game. Even if the source code and other materials are available, old games won’t work. This is because the services are already archaic.

Intellectual Property

This is another important issue with old game preservation. Museums have to consider if preserving the game is a violation of a company’s intellectual property. That’s the biggest problem he’s facing right now, Young said. “The situation is getting worse because many games have to be played online. Once the game company shuts down the server, all players have to go…handling such game becomes illegal.”

Berman mentions that there are exemptions in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act in the United States. For example, when a company no longer runs an official server, researchers can circumvent copyright protection and let the game run again. “Tron Evolution” is an example, but this is rare. “We can get around the restrictions at the legal level,” Berman said, “but it’s technically too difficult, it’s time-consuming and labour-intensive, and it’s a problem with a lot of games.”

In the United States and Canada, laws appear to allow academics to make copies of games for study and research purposes. But Young said that right has yet to be proven in court. Those working on game conservation are not yet willing to take the risk. Unless enough agencies do it and don’t get sued (or win a case), no one dares to promise that this will work. How to save online games perfectly has always been a very troubling problem

Gaming history is at risk of disappearing

Berman specifically mentioned the difficulty of game preservation

“A lot of people start from scratch when they change phones, so whatever games they have installed on their phones are completely gone. Getting the data itself is quite difficult, not to mention that there are so many different brands of phones on the market. For example, the way data is obtained from a Razer phone and an LG Chocolate phone is very different.”

New technologies such as cloud gaming have further increased the complexity of preserving old games. Still, Berman seems to have come to terms with the fact that he doesn’t think there’s any perfect way to save all games. “If the goal is to keep a playable version of every game, we’ve lost. We’ve realized that some games may never be seen again in the future, and there’s no way to save a certain game unless we work with the developers. But even if you get a copy from the developer, the experience of playing on a local console is different relative to the cloud.”

Videos of old games?

The result is that in the future, people will most likely not be able to actually play certain games. Saving the game itself is only the first step. It is more difficult to restore the game equipment and scenes.

“It’s going to be a lot more difficult for conservators to preserve the game because we can’t do the old ways,” Young said. “I think over time, there will have to be a variety of different ways to preserve history. Recording videos, writing oral histories, etc may come in handy…”

Berman feels the same way… “Video is going to be a powerful tool, especially for games that don’t run on emulators. It’s better than nothing. Of course, I’d like to keep playable versions of all games, but that’s not realistic. 100 years later, watching a video may be the easiest way for people to learn about a game. A lot of games are not so popular with players that no one wants to play it again, maybe only the video will last for a long time.”

Game preservation for profit?

Of course, not every conservator’s plan is this big, and perhaps it’s more important to take the first step first. In 2022, Swedish publisher Embracer Group launched its own game archive, which now houses some 50,000 games, consoles and accessories. In order to obtain and maintain physical versions of all published games on the market, the publisher employs 5 dedicated staff.

“Our venue is large enough because we are ambitious and want to collect a lot of games, game accessories and hardware,” explains Natalia Kovalainen, Embrother’s chief archivist.

Unlike schools and nonprofit museums, Embracer’s project is run by a for-profit company. However, Kovalainen claims Embracer wasn’t thinking about how to make money by building an archive of games. “In our view, we are trying to promote and preserve games, gaming history, and culture, and someone has to do it. Right now, this project doesn’t generate any financial benefits. We also don’t know if we’ll be able to make money from it in the future. It’s not our original intention, we felt it was no different from any other cultural institution or library.”

Berman is happy with Embracer’s interest in saving games. On the one hand, he hopes that more large game collections will appear around the world. On the other hand, he believes that the best cultural relics protection often starts within the company.

Professional division and cooperation

While the Embracer and Strong’s National Museum have completely different approaches to preserving old games, Berman welcomes “newcomers” into the field. “Other organizations and teams have their own focus, which will help people understand video games more fully.”

Embracer specializes in collecting physical games, including versions of each game released in different regions and languages. “This will be one of our main advantages in the long run,” Kovalainen said. “It’s exciting for researchers to compare versions of the same game.”

The Cyd Bolton Collection focuses on games released in the North American market. Chris Young said that the University of Toronto-Mississauga especially hopes to collect the “artifacts” of the game industry in Toronto and Ontario.

The collection of the Strong National Museum is more international. Berman notes that he has hosted Japanese researchers who have found that the Strong National Museum has a larger and broader collection of older Nintendo games sold in the Japanese home market than Chinese museums.

Over time, different schools, museums and private institutions will collaborate more closely.

“Right now, there are still too few institutions doing this work in any substantive way,” Young said. “In other areas, such as books or film, there are more institutions that are collecting older works and more people…”

Kovalainen believes that collaboration is critical no matter how institutions preserve old games. “It’s very important for us to be a part of the whole community because it takes everyone to pull together, we can’t do this alone… No one can do everything at the same time, it has to work together.”

Berman adds: “Developers should keep the source code, design documents, videos of their work, and get in touch with specialized agencies rather than putting them on auction sites. We’re happy to offer advice and accept developer donations. We’re here to help. The game industry needs each other to preserve old games.”